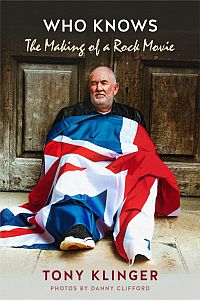

I recently had the opportunity to read the wonderful book by Tony Klinger, ‘Who Knows: The Making of a Rock Movie’, which explains the concept and experience of making the movie ‘The Kids Are Alright’ with The Who. This is the third edition of the book (previously available initially as ‘Twilight of the Gods’ and then ‘The Who and I’) which has been updated with more text and photos and is a warts and all description which is fascinating to the casual fan and absolutely essential to lovers of The Who.

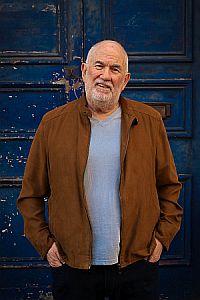

His writing style is clear and concise, full of descriptions which make the reader they were witnessing the events firsthand and he pulls no punches at all on his views of the band and those involved with the film. I was fortunate enough to be able to catch up with Tony, and I hope the insights below get you intrigued enough to seek the book out for yourselves as it is an in-depth look at one of the world’s most iconic bands just before the death of Keith Moon.

Kev Rowland: Who, what or when is Tony Klinger?

Tony Klinger: I am a person who is creative, but with a scrambled egg brain. I am almost compulsive about a crazy work ethic, more because I love it than I need to, although there have been times when I really needed it. My first influences and memories are family. Warm, loving but very determined to move forward. Because of my background, with a very working-class family historically, my grandparents all having been Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia and settling into typical jobs of the working class of the early 20th Century. One lot had a sweatshop making kiddies duffel coats for a big chain store and I remember them making the cabbage (the allowed pieces of spare material if you had a good cutter) and it being lowered on a hoist over the stairs for my dad to sell in Shepherds Bush Market to make some cash. He was an engineer in his day job and had been drafted into that as a reserved occupation despite volunteering 11 times for the Forces, but he had no money and by the end of the war had my older sister to support along with my mum. His dad was a tailor's presser, a smashing little man, strong as an ox who my dad said worked like a donkey. He was always working until my dad made him retire. My dad and uncle slept on the bench on which he pressed. If he had to work 20 hours they could only sleep for 4. They lived in Soho which was divided into a Jewish, Irish and Italian areas. Nothing like now, but more like New York at that time.

I won some prizes for writing at the first private school I attended aged 8 after my dad's career started to take off like a rocket. I won one national competition and tied with the girl sitting next to me for the other around the age of 9 or 10. It was from Cadbury and Nestle chocolate and a man came to our school and many others I suspect, showed you a film about how they made chocolate, and we were asked to write an essay about it. The prize was a lot of chocolate and a visit to the factory. It made a very huge impression on me as a little boy. I knew, straight away that I wanted to be in the film industry and to write for it. I just didn't know how to do it. My next step was, at aged 11 to write, edit and publish my senior school underground magazine, ‘Fanfare’. (We were recently sent digital copies of some issues dated 1961 by the school's alumni) - I did it anonymously until I was discovered and punished by the school. But I had the bug big time, and it has never left me. I wanted to communicate with as many people as possible.

KR: What made you decide you wanted a career in film? How big an impact was your father, Michael?

KR: What made you decide you wanted a career in film? How big an impact was your father, Michael?

TK: I've kind of answered that question above but I will go further. The second part first. My father wasn't anywhere near to going in the direction of the film business when I first knew that was what I wanted to do. In fact I childishly resented it when he did go that way because at the time he was a night club owner. My dad was more of an influence through his love of and knowledge of films, particularly his deep affection for foreign films. Remember he had continental tastes inherited via his parents. I got that to from him, so I have always been very keen on great French, Italian and German cinema, along with British films - not just reared on American studio pictures.

When he went into films it started with an accident that turned his idea from a club to an initial one cinema in Soho and that developed into a chain of cinemas and an unreal rapid explosion into the distribution business and then via some pretty poor exploitation films through to progressively bigger and better films as he found his feet and of course it’s obvious from those films what his underlying taste was.

Put another way, he backed through business into becoming a very sophisticated and astute film producer. But that, and his uncanny ability to finance, sell films was to come much later than my entry into the industry from the other, creative end.

Where we met, sometime later, in the middle, was when I realised just how good he was at producing and what an awesome script editor he was and he told me that one of his directors, Peter Collinson and a novelist, Wilbur Smith, told him to read some of my scripts that they recommended to him. It transpired that he hadn't really read my writing until then. It was after that, when I was already 34 or 35 that we went into partnership and merged our activities, and the following three or four years until he died, was the best fun of my life. Not the most productive but the time we both realised we were each other's best friend.

KR: What was it like working on the iconic series ‘The Avengers’?

TK: The first reflection is that for the year or so I worked on ‘The Avengers’, other than for day exteriors, I didn't see daylight. I was always first into the studio and last to leave. It was an opportunity to take advantage of any gaps and leverage myself in so that I could get more experience and seniority. I learned how to work in a union closed shop which I found the most stupid thing I had ever encountered but which we all had to live with.

I got to have ridiculous inflated responsibility because of my hyper energy. It got noticed by our American bosses who came over and called me up to the big office upstairs to meet the kid who was earning more than the producer because of his crazy overtime payments. They instructed me to stop doing overtime that day and although I tried to explain that I didn't fill in my time sheets, the union shop stewards were doing so and pegging other people's time sheet to mine as I was the longest hours person there. I also said that it was me getting up to our 5 units ready to go out to various locations and if they weren't ready to shoot by 9.15 the costs of overtime for entire units would be enormous. Of course they didn't listen to a 17-year-old kid and the next day I came to the studio at the designated unit call time of 8.30 and no unit was ready to shoot until about noon. I got called back to the office that night and instructed to go back to my previous call time.

I found I got along with actors and they with me, in fact the two stars. Pat Macnee and Linda Thorson, were extremely supportive when the producer screwed me over. I don't think he really had a problem with me but whenever my father was featured in a trade journal, he'd pin it onto his office board and circle the stories in red. He was clearly jealous of dad. When he made his move on me and told me I had effectively dismissed myself I was about to go when Pat asked me where I was going. I explained what was happening and he told me that he and Linda were taking me for a special lunch. It was only around twelve so I was surprised but then he told the producer's office that he would not be coming back from lunch unless and until I was reappointed to my job, but also with a wage rise. And that's what happened.

Of course this is just a potted version of what was a fabulous experience that you couldn't learn any other way. Remembering this was the biggest and best TV series in the UK and one of very few that was also a hit in the States.

KR: How did you migrate from making films and documentaries into music?

KR: How did you migrate from making films and documentaries into music?

TK: I was a big music fan. I loved to dance and fancied myself with my Cuban high heeled boots which made me well over 6 feet something, together with, can you imagine it, a black sombrero, a white Nehru three quarter length silk jacket and hipster flared trousers. Of course I was smoking little black thin cigars; and choking to death. But I looked very cool, or so I thought. Now I realise I must have been like a streak of piss weighing in at under 140 pounds. I went to every club that would let me in and although I didn't do drugs, I was regularly drinking too many drinks and like most of my friends, regularly getting sloshed. I went to Samanthas, The Cromwellian, the Bag of Nails, and many others including the Marquee to see live bands.

That's where I first heard and saw The Who. I think they were already called by that name, not The High Numbers. I was knocked out by their attitude more than their music the first couple of times I saw them. I didn't find it easy to dance to their music so that made it difficult to pull girls, and as that was my prime concern aged about 15 or 16, they weren't my number one group. It was easier to dance to Motown. In fact, I could say the same for some of the terrific acts at Eel Pie Island, including The Rolling Stones, although Mick Jagger made us laugh. He looked so odd, but the women clearly found him very sexy. I don't think that was ever the vibe with Roger. It was a long time later that I realised just how good The Who were as musicians. Initially I wasn't a Mod and that seemed to be the ticket to being a true fan. In fact, I had similar problems with their nemesis, the Rockers, because I really liked what was to become heavy rock or metal, so I was somewhere in between. That meant when The Beatles were becoming big, they became the act for almost everyone. They weren't pigeonholed like the others. I liked the message of searching, love and all of that, and I guess I was leaning towards being a hippy in the California style. Like millions of others I idolised all things American at the time, it seemed like the centre of the world but it was exciting to be part of the British culture explosion as I started to make films and got to go to America where the people said, " I just love your accent.." and where they said, quite openly, that they trusted the word of an English person.

I didn’t have any kind of strategic plan to move from one segment of production to another. Like water finding its own path I went, like most freelancers, where the work was. However this was also influenced by personal likes and dislikes. I loved music and like many other contemporaries was heavily influenced and moved by the rhythms of that incredible couple of generations of music and lifestyles in the 60’s and 70’s. I also discovered that through my making of my early documentaries I had direct access to leading new and established musicians whose work I wanted as the soundtrack of those films.

I met and worked with the leading music publishers, record companies and musicians. And I suppose this is very relevant, we got on great. We chose early tracks from groups like Supertramp, Arc and Crucible and negotiated their use for our films at very favourable terms because they wanted to help me and my ambitions. There’s a whole saga after we’d agreed a great deal with the guys from Supertramp for ‘Extremes’ when they’d finally turned up to see our film. Even though they’d not released anything at that moment I knew 100% that they were special and had a big future. At the time they hadn’t got any definite funding and someone from their team called us and said if we could give them a few hundred pounds more we could have a share of the publishing of the songs we’d selected. We didn’t have any money, so we went to our film’s financing, its distributor, and put this great offer to him. He got really angry and told us to f…. Off from his office and stuck to our job of delivering the film. Hence, we had no share of Supertramp’s success. The next time I saw them and their manager, was many years later when we were all playing for our Showbiz football team when we were living in Los Angeles.

KR: How did you get involved with Deep Purple?

TK: It was from those types of connections that I first got to make some low budget pop promos (now you’d call them rock videos) between my other projects. I found it was something I had a natural empathy with. I got along with musicians, and they got along with me. I had a good sense of rhythm, and this strongly influenced my style of film editing as I edited most of what I shot. This editing work put me in the cutting rooms next to the men editing work for a little group you might have heard of, The Beatles. And although they’d probably not remember us, we got to meet all their team and again that put us in that world. Funnily enough years later when we were editing ‘The Kids are Alright’ we were in the next cutting rooms to Thelma Shumaker editing ‘Wings Over America’. Paul asked to see our edit and as a courtesy we said yes, after which he supposedly told Thelma to start their edit from scratch again. I can’t imagine what she thought about that because she’s one of the greatest editors of all time with films like ‘Raging Bull’ to her later credit.

During the making of my early films, I got to meet a whole bunch of music people searching for music tracks for my productions, that I could afford, which was very little. I met the leading publishers, record company executives, managers and groups, and some of these contacts ended up asking me to make what they called pop promos. I don't know where these are or were used for, but someone once told me that these very low budget little productions were used to promote their acts for overseas labels and tours. All I knew was it was fun, paid the bills and I learned a lot from them.

I got to meet the music engineer, Martin Birch, who later went on to become one of the most successful and prominent hard rock record producers in the world. We became very good friends, and this led me to meet the management of Deep Purple. At the same time I had agreed to team up with a business man who saw an opportunity and he arranged for us to work with elements of that band for me to direct, write and produce a film, ‘The Butterfly Ball’ based on the music of Roger Glover and the words of Alan Aldridge to be ready as the live part in the Albert Hall by Vincent Price with the London Symphony Orchestra. I got very excited by this project and between us we agreed a script and a budget for about $100k (which in today's money adjusted for inflation is $664,000) a not insubstantial budget. We got busy hiring a dance troupe, arranging for a week's rehearsal for them, we searched out the lady who designed the wonderful costumes for the movie Beatrix Potter etc.

In addition to all of this, and more or less in the same timeframe, the management asked me to pull together the Deep Purple concert being filmed in the Budokan stadium in Japan. I was in hyperactive mode but ready to go do it all. Imagine how I felt when the management called me in the day of the dress rehearsal and told me, out of the blue, that the budget had to be cut by three quarters to about $25,000. But they wanted me to deliver the same film for one quarter of the budget. They also told me they didn't have clearance on the poems so I shouldn't film any of the preliminaries and none of the poems being read by Vincent Price. Now I could walk away but I had hired 13 crews who were relying on me, the person they knew. I couldn't let them down. Instead, I let myself down. The film's ingredients were eviscerated and, as my late father said, "and you can't put a credit on the film explaining why the dancers are too limited, or the costumes come from a fancy dress show. You took a wrong decision by accepting how you were shafted so now you have to suck it up, but never make the same mistake again."

I wanted to cut the film down to just a TV hour of the concert because the material we'd shot elsewhere really disappointed me as we just had no money so the results were very hit and miss. But the film's distributors wouldn't accept that because we had signed to deliver a 90-minute film so that was what they demanded. Another lesson learned.

KR: What led to the initial meeting with Roger Daltrey?

KR: What led to the initial meeting with Roger Daltrey?

TK: It was pretty much straight after that battle where we did manage to get distribution on the Rank circuit and got the investors their money back, when I was approached by another music friend, the composer David Courtney alongside another business associate, the ex-agent Sydney Rose. He knew and understood what had happened with Deep Purple because he'd also been screwed in the past by others. He was producing the ‘One of the Boys’ album with Roger Daltrey and asked me to listen to the demos of the tracks. I thought it was excellent and he suggested I would be the right person to make the video for the title track. We met them for lunch, which was a bit more like a grilling by Roger. We got on great, but I was really insistent about the budget being agreed and paid upfront which was a hangover from the Deep Purple money issues. We went away and I wrote out a little script and some matchstick men drawings and, of course a budget.

I had a face to face with Roger who cross examined me and my ideas but then signed off on the project and directed me to meet with Bill and Jackie Curbishley. He was, as ever, very tough and direct, while Jackie was a really nice person. We went forward to receive the funding, as agreed, and then to film what I had scripted. Roger confronted me on the first shot, not wanting to stand with his back to camera, not really understanding that I was shooting through the mirror onto another mirror that would shatter, all the images I was going to portray him wearing. No VFX in those days, it all had to be done mechanically. He was refusing to do as I asked. I told him that was my decision as I was the director, or I better walk away, and he should direct. He said he'd do it but if it was a fuck up it was all down to me. We went ahead and after we got over that bump, he was happy to take my direction and was pleased with the video when it was finished. It went on to be played all over the States in a very big release but that's all another story.

KR: It is very clear in the book that your initial ideas for the film and the final product are very different indeed. Can you explain your vision and what would have happened if you had been left to your own devices and followed the original concept?

TK: There are glaring differences between my initial ideas and the final film. That divergence started to happen when Jeff Stein was introduced as the Director when we both had contracts to do the same job. Because of my previous experiences I wanted to walk away but for reasons I expand on in the book didn't do so. Stein had his own ideas which were more organic and deriving from existing researched material. I wanted to make a modern version of a Marx Brothers film like ‘Hellzapoppin’ and that was one thing which Jeff and I did find agreement on. What happened next to that compromise was the reality of budget constraints, different groups within the band and the factions on the film production meant the concepts weren't realised.

However, the bits that were filmed did work pretty well and the research and negotiations were really successful beyond our expectations. We ended up entering something like 170 contracts - together with those mountains of material and the problems we had balancing the egos, the music mixes and other issues we could still be making the film unless someone called stop to it.

It was a very difficult production to deal with. By that time, I had been in charge of some very big feature films as well as a great deal of documentary and music work and I had to swallow real hard to get through some of the craziness. By the time we were making the big decisions I was either very involved, partially or not at all, depending on the flow of the tide. In one way I think Jeff's concept of just letting the crazies do their thing in front of our cameras worked out for the huge number of Who fans in the world who would appreciate the honesty of that vision. I wanted to make an interesting construct to reflect how society was changing and saw this film as a vehicle to show that. We both won and lost.

KR: With the value of hindsight when did the film start falling apart and moving away from the original ideas, and why was that?

TK: As I wrote earlier the film started falling apart right from the get-go. The idea of two camps within the band appointing their own director, Stein and me, and then wanting the two of us to fight it out between them was not a great idea. In fact, it was a San Andreas fault line that could never be papered over. My battles with Jeff really were just an echo of the bigger battles for dominance of the band between Pete on the one hand and the other members of the band on the other, led by Roger. It was a battle for dominance of The Who with Bill being the manager of that very difficult balancing act.

I said this without the benefit of hindsight. I knew and spoke openly about how these schisms were hugely destructive to the film's production. These observations of mine were misconstrued and called "sour grapes" by Bill and others. It wasn't intended to be since I didn't dislike Jeff but simply questioned the choices being made. The more I pointed out what was happening the more I was criticised until I was effectively muzzled and eventually ignored. it wasn't until after we wrapped that various people, including Bill told me I had been right about many of the things I had stated for the record. That didn't help in any way as you can't remake the past but it’s gratifying if we all learn from it and grow.

At the start of the project, I am not sure anyone on the film except me had a real idea of what the specific roles of a producer and director are. Therefore, the titles were getting confused and thrown around too much.

KR: You worked very closely with one of the world’s greatest rock bands just when they were falling to pieces, yet on their night they could still be the best band in town. How would you describe each of the guys during that period?

KR: You worked very closely with one of the world’s greatest rock bands just when they were falling to pieces, yet on their night they could still be the best band in town. How would you describe each of the guys during that period?

TK: You've heard the expression that the Who were three musical geniuses and a great rock singer. That's how I saw them and still do when I consider that era. I almost didn't see them as individuals until we were filming them individually.

Pete and I had virtually no relationship because he seemed keen to ignore me whenever possible. The times we did interact were rare but mostly very brief and I don't think he really had much of an idea of who or what I was or did. I think I was like a fly buzzing in the room, a minor annoyance. A reminder that he hadn't totally won the argument about the choice of Jeff as director since I was still around and that appeared to bother Jeff so in turn Jeff and Pete kept me as far away as possible. I recognised his musical genius but would have loved to discuss on camera with him what the back story was on some of his work like ‘Tommy’ but it wasn't to be. The few times we communicated were either abrupt or confrontational. But all that being said he is one of the best and most influential composers of his era. A total original and a terrific showman. I'm just not sure how much of that angst was for real and how much of it was an act?

John was a strange bird. I had my major run in's with him in the studio because of his anti-Semitic cartoon which I found totally racist and unacceptable. I know it was late at night, and he was probably high but that isn't an excuse. I couldn't accept him as a reasonably civilised human after that, I dealt with him professionally and he was polite with me before and after the incident at the studio. No question, like Pete, a musical genius and the best bass player of them all but as a person I found him too dark for my taste.

Roger is the band member I had the most time for and with as a regular person who I felt had his feet on the ground. He is one of the greatest rock singers there has ever been and epitomises the working-class boy who found his path to glory which could only come from something like a gift as a musician or a sports star or like he often says, as a villain. There's always something humorous or al little dangerous and challenging behind those blue eyes!

Keith is frozen in time for me because he died too young but entirely predictably. He's like the sign on the tombstone of Danny Fisher in the Harold Robbins book, "Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse..." How do you catch mercury and control where it flows? The answer is you can't. I am still fascinated by him and his childlike nature which I largely found funny and endearing but sometimes aggravating. He could be and was five or six different people in one day. He was the epitome of a rock star. Good and bad. But I aim to tell much more about him soon, so I won't go too deep just now.

KR: You stayed working on the film later than planned, but still left long before it was completed. Do you regret leaving when you did, or do you feel you should have done so earlier/later and if so, why?

TK: Left is maybe the wrong word. I felt I had earlier tried to resign, and then later felt my position had become untenable. Progressively I was listened to less and less. It didn't make me feel any better knowing that what I was warning would happen was happening. I had taken a firm stand based on my knowledge and experience. My job had evolved into producing the film and that became ever more difficult when all the decisions and money came via the band's management. Anything I tried to do was being second guessed and undermined since it came from me rather than it being right or wrong. I was aware that anything I commented on would be considered as sour grapes based on the fact that I was no longer to be the director. In fact, that was never true, but I figured that it was another means of other people getting their way. Put another way, if Klinger said something it must, by definition, be wrong, and therefore, following that logic, the opposite would be of benefit to the band and the film.

I don't think that the entire band bought into this, but clearly Pete did because Jeff was his man. And if Pete did then Bill was not going to rock the boat too much. Some of the time there was hope when others in the band asserted themselves or Bill took a different view but as time progressed it became clear that he had a different agenda. He seemed to have ambitions of becoming a film producer and this was a means to doing so and establishing a track record. I never had that as a conversation with him or whether it was a pure coincidence that this opportunity simply coincided with that aim of his.

My leaving eventually came about when I was informed that I shouldn't come on the set for the shoot with a small group of fans at Shepperton. I attended anyhow but definitely felt the cold shoulder. By this time everything and every move I made was more than open to question, and accountants were checking every penny of our spend but although they never found anything wrong with a single penny from my end, they turned a blind eye on many of the questionable expenditures that were still continuing that we had pointed out. Bill brought in a couple of other people to "help out" and it was clear to me and Sydney that these guys, however well-intentioned they were, only had an interest in seeing the film finished and costs being contained. Strangely neither of these tasks were to be accomplished as the film meandered to a very long and costly music and sound mix in L.A. in which I was not involved.

Had I remained functional in my producer role I would have done some stuff differently and one of those things would have been to keep all the sound mixes, including the music, in London which remains one of the best places in the world for that type of work. This would have saved time, money, transport and aggravation. It would also have been just as good if not better.

Therefore, the time of my leaving was dictated by others but in retrospect I couldn't have done much to change it without the support of Bill who had, at that time, another view.

KR: You came back to undertake some work to get the film over the line, but in hindsight do you feel that was the right thing to do given it was so far removed from your original idea?

KR: You came back to undertake some work to get the film over the line, but in hindsight do you feel that was the right thing to do given it was so far removed from your original idea?

TK: I returned because I was asked to do so by Bill and felt honour bound by my contract to do what I could, particularly when he'd voiced the opinion that I had been right in some of the things I had predicted or said. But going back was very disappointing. It was like returning to a lover who has been unfaithful. You might still see her beauty but feel sullied by the fact that she had been intimate with another. Put another way, I no longer felt passionate about our film and felt it had become more just a professional project. I already had enough aggression, anger and confrontation on the film without revisiting it.

Because of my previous exclusion there was also a little enjoyment on my part due to the discomfort of some others at my return and redemption. On reflection I think the Tony of today would not have returned and on balance that would have been the right course.

KR: What have you been doing with your career since the film was released?

TK: My career took me to the States pretty much after this film. In that immediate period, I produced a couple of features in the UK and then left for Los Angeles for a few years with my family. We had a little company there and it was a very different environment, both good and bad. Then I worked for a while on two small public companies, one making films and the other TV movies of the week. We were active but it was a very different way of doing business. There was the business of our businesses, and then there was the share price of our stocks. One didn't have much to do with the other. For instance, the film company had an initially low share price but generally made a profit. The shares remained low. The TV company never made a real profit, but the shares really went up. I asked market experts, and they explained that the TV company had the sizzle, which smelled like it could be exciting, whereas the movie company was a steady earner but not likely to suddenly make huge profits. The share guys told us that investors in that size company preferred the sizzle to the steak.

I got fed up with this around the time my dad died which was toward the end of the 80's. I didn't want to be a purveyor of steak and the corporate game was not for me. Almost straight after this a man I knew with a big film and TV library asked me if I would head up his new production arm. I was flattered and was going to do it, selecting the colour of a new Mercedes and finding a nice house in Pacific Palisades before I realised that I was stepping out of the frying pan into another, and very similar hot fire. I said no and we collected our family and headed back to the U.K.

Almost immediately I was asked to return to Malta, where we'd made a couple of films, to assist with putting together and marketing elements of the studio. It was a delightful 6-month contract and was followed straight after by a Line Producing job on a film to be directed by Brian Hutton. We travelled back to Malta and Italy and Israel doing deals and finding locations. It all went great until the finance fell through.

I was all out of love with the film business and had lost my love for certain parts of it. I found myself without direction. Shortly after that we were driving our kids to a show in London when our car phone rang. It was like a house brick if you can think back that far. It was the Bournemouth Film School offering me an interview to be an Associate Lecturer. My wife had made it happen and, for the first time in my life I was interviewed because I had always been the other side of the table. I got the job and during the next decade became an academic and rediscovered my love and passion for film making from the kids I taught, it was contagious.

During this period I had 13 promotions and accolades including Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Course Leader of Kickstart, Course Director MA Film Production & Foundation Degree Film Production, Visiting Professor, Visiting Fellow (Leeds Met), External Examiner, OUVS (Open University Validation Service) Process Panel Member, OCR Assessor at various institutions including The Bournemouth Film School (now part of the Arts Institute Bournemouth) The Northern Film School (now part of Leeds Beckett University) and Director of the Media Production Centre, Talent Lab and Media Hub (University of East London). Taken together my students won 19 major awards nationally and internationally such as the Queens Anniversary Award for Education, Kodak Prizes, Fuji Prizes and the Tel Aviv international film student prize, largely considered the World Student Film Festival where our small college beat national film schools from around the globe. After all of this I was honoured to be appointed the National Secretary of AMPE (the Association of Media Practice Educators) which invited me to be the Chair and Keynote speaker for our national conference.

After this I discovered the awful truth about being promoted away from lecturing to students evolved into conducting meetings about meetings for around half of every week. it was time to go. As allowed for in my contract I purchased two of my own Directorates to form a commercial company, TLMH. We produced test commercials, and some small films plus developed a new technology for mobile phones which we were able to sell into some huge organisations such as ITV, Manchester United and many others. As the company developed, we attracted investment which we accepted. They demanded we drop our creative production arm and focus purely on the digital development. I refused and lost that argument leaving my own corporate baby to their care.

KR: The book is somewhat unusual in that unlike most rock memories it covers a relatively short period of time and pulls no punches when discussing what happened and the individuals concerned. What did you want to achieve with this?

KR: The book is somewhat unusual in that unlike most rock memories it covers a relatively short period of time and pulls no punches when discussing what happened and the individuals concerned. What did you want to achieve with this?

TK: In retrospect if I achieve anything meaningful my book will be to help those with the aim of getting into the movie business to understand some of the reality surrounding the glitz and the glamour. But the initial motivation when I started this book's creation was to let out the poisonous bile that was contaminating my soul. I needed to get it out before it did me some long-term harm. I told the truth, then and now, even when it demonstrated some of my own errors and misjudgements. Obviously, I arrive at conclusions and opinions are like anal orifices, everyone has one.

KR: What’s next?

TK: My next chapters of life continue to be as exciting. I have several books both new, and the third edition of ‘Who Knows, The Making of a Rock Movie’ which is available worldwide now. Coming very soon are, ‘How to Get Into the Movie Business’ and ‘How to Get Your Movie Made by Someone Who Knows’. More announcements to follow later this year.

I also have four film documentaries on many streaming platforms and their releases are widening out. These are ‘The Man Who Got Carter’, ‘Solo2Darwin’, ‘Sisters’ and ‘Dirty, Sexy and Totally Iconic’ and there are more on the way.

We are in the process of creating another Web/app called Give-Get-Go Education CIC which will be available for people aged 8 to 18 to learn online in a fun manner about FILM, THEATRE and EVENT MANAGEMENT. We already had the successful "Tony Klinger Coaching" which hosts small groups and the occasional one to one coaching service but we are about to launch "Tony Klinger Online Coaching" for an unlimited number of participants. We want to share our company motto, GIVE your ideas, share GET help, GO do it (Give-Get-Go) We believe that young people, under 25 and older people, over 55 are too often ignored so we give them priority although we are not ageist, in fact I believe that talent doesn't know where it comes from, has no religion, race or creed. You could say Tony Klinger is still open for business, the movie business.